* On your first PCB Assembly order!

* Up to $300 discount

C - A L L E Y

C - A L L E Y

About Us | Events | Company Structure | Management Staff Structure | Market Focus | Company Certification | Our Services

Even with autorouters, accurate design schedulers need to consider soft issues.

When I first began laying out printed circuit boards, giving estimates was reminiscent of the movie The Money Pit. The engineer or project manager would hand me a schematic (or netlist), and ask, “How long to do the layout for this?” My reply was invariably, “Two weeks!”

When they came back after two weeks and asked, “Is it done?” the answer, of course would always be “no.”

“Well, how long until you finish it?”

“Two weeks.”

Unlike the movie, though, my reply was out of ignorance on how to estimate schematic capture and PCB layouts.

Indeed, I have been asked many times through the years how to estimate the amount of time it takes to do a board layout. There is no simple answer to this question. The algorithm and method I use have evolved over the years to what they are today.

When I first started doing PCB layouts, we used light tables and Bishop Graphics tape and “dots.” The company I worked for usually had large contracts, and the amount of time it took did not really factor in overall to the cost. As a result, the question “how long will it take?” was not that important, and was more of a scheduling issue.

My introduction to computer-aided design layout came when I transferred to a group that was using PCs to perform electronic capture of the schematic and then create the PCB layout on a computer using CAD software. The initial CAD was on a blazing IBM 6MHz AT computer, using some sort of bridge board that ran Unix software. The operating system and program resided on 16 5-1/4" floppy disks.

I well remember the computer going haywire and tech support telling me to “reload the OS.” This process took two or three hours of feeding one floppy after the other. I soon gave up on calling tech support, cutting out the middle man, and would reload the software when things went awry. This, of course, did not bode well with upper management, who expected a layout to be finished in a timely manner.

The group I’d transferred to created space flight computers and hardware. When they asked “how long will it take?” it was still a scheduling question, but the answer was more important because, if you did not finish the layout on time and give the engineers some hardware to populate and program, you might miss the flight into space on that rocket.

I also attribute this “get it right the first time” attitude to working in this section, as I was often told that if there were any issues with the PCB, I would be sent to fix them. In orbit. It was meant as a joke, but I got the point, and always strove to have an error-free layout. (There also was a contract and funding element, as management’s quote for the project was sufficient to do only one spin of the PCB.)

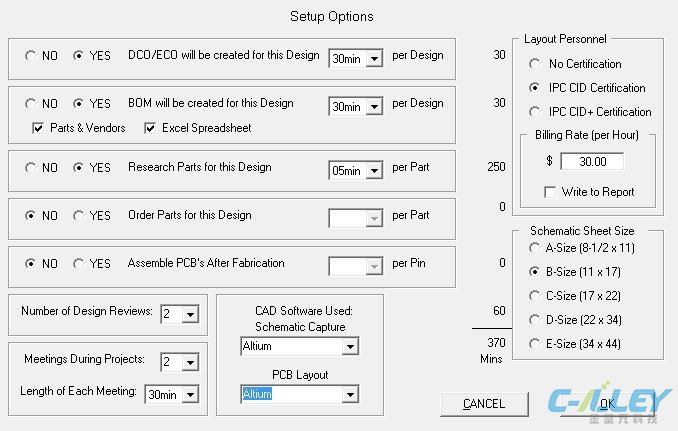

FIGURE 1. In the main form, a user enters the number of pins and the x and y dimensions.

The Myth of the Autorouter

In its efforts to cut down this “two weeks” turnaround time, I recall management thinking training would be helpful. The issue, however, was the instructors were also expected to help me complete a layout during the five-day training class. Anyone who has attended training for CAD software will attest five days are usually just enough time for instructors to conduct the training, with no time left for additional help. So when I came back from class, their question, “Did you finish the layout while in class?” was met with a “no.”

Eventually, management realized the CAD software we were using was barely able to keep up with demands, and we upgraded to a much larger CAD hardware/software package. This Unix-based software was awesome for what it did at the time, but I was still giving estimates of “two weeks.” The other issue was this CAD package also came with an autorouter I was expected to use, to shorten that two-week estimate to something like two days. After all, all I had to do was press a button, and the computer would do the rest, right?

Not quite. I remember using the autorouter on the layout of a very dense board. It had something like 12 layers for planes and traces. I remember getting it set up and pressing the autoroute button. It would take no fewer than 23 hours to run the course of route, rip-up, route, push-and-shove, etc. I could come back the next day, and the routing would be about 89% complete. That left me with whatever the autorouter could not complete. This was not too bad, other than the router did not conform to any grid I was using, and so any leftover routes required more work to complete than would have been needed had I done the routing myself. It also led to another unexpected “feature.” The engineers, now realizing I could autoroute the boards, would add changes to the schematic and design at the last minute. After all, I could now autoroute the board in 24 hours, right? CAD designer frustration ensued.

I left this company to work for a service bureau in a nearby city. The owner-manager of the company already had a spreadsheet on his computer that he would use to create an estimate, but I was interested in how to create this estimate separately. The question was compounded by the addition of us also creating the schematic for some clients.

Somewhere along the way, I snagged a set of service bureau forms, which had distilled the estimation to a fill-in-the-blank process. I copied these forms many times and used them initially to assist my layout estimates. I could not understand the algorithms used, however, as they did not seem to be a linear estimation of time. Starting with the number of pins and the board size, it was determined how long in hours (or days) it would take to create the layout. The time varied based on density. There were also upcharges for expediting the layout.

I would sit at a local coffee shop in the mornings working through the numbers, trying to decipher the process for estimating layouts. Then one day it made sense. The algorithm took into account factors beyond the number of pins and board size. It took into account the amount of time every job has for setup and processing (or housekeeping). Once I figured this out, I set about to create my own algorithm based on my own capabilities.

My first attempt resulted in a set of forms similar to the service bureau forms I’d “borrowed.” It was a two-page set of forms where the prospective client (or me) would fill in the numbers, generating a layout estimate result in hours (or days). I used this set of forms, but soon realized there was a repetitive nature to the calculations that was best-suited to an automated process (read: computers). I also realized the solution needed to be portable, so if I were at the client’s office, I could still access this information to create an estimate.

FIGURE 2. At the setup screen, options such as schematic size are input.

Please send Email to kspcba@c-alley.com or call us through +86 13828766801 Or submit your inquiry by online form. Please fill out below form and attach your manufacturing files( PCB Gerber files and BOM List) if need quotation. We will contact you shortly.

+86 13828766801

+86 13828766801 kspcba@c-alley.com

kspcba@c-alley.com https://www.kingshengpcba.com/

https://www.kingshengpcba.com/ 2/F, Building 6, Tangtou 3rd Industrial Zone, Tangtou Community, Shiyan Town, Baoan District, Shenzhen, China, 518108

2/F, Building 6, Tangtou 3rd Industrial Zone, Tangtou Community, Shiyan Town, Baoan District, Shenzhen, China, 518108